“Tim, take your hat off.”

A simple request accompanied by a stern glance my direction from the Samoan man sitting cross-legged on the floor. He is built like a battleship and I feel my spine go limp with shame.

Almost two-weeks prior, in this same location, I’d learned that wearing your hat in the fale is disrespectful. Yet, like the flaky palagi I am, I’ve forgotten. I remove my hat, flustered at my oversight.

It’s no wonder I’m a little distracted. I’m watching my partner, laying on her side on a woven mat a few feet in front of me. She’s being held down by several Samoan men. The stern fellow who asked me to remove my hat is leaning over her. He is repeatedly tapping a sharp blade fixed to the end of a small wooden handle into my partner’s flesh. I know she wants to squirm, but she’s pinned down. I’m pretty sure she also wants to scream, but she keeps a lid on her agony. How did she end up in this situation? Furthermore, why am I passively watching her be tortured?

The word ‘tattoo’ comes from the Polynesian word ‘tatau,’ meaning to write.

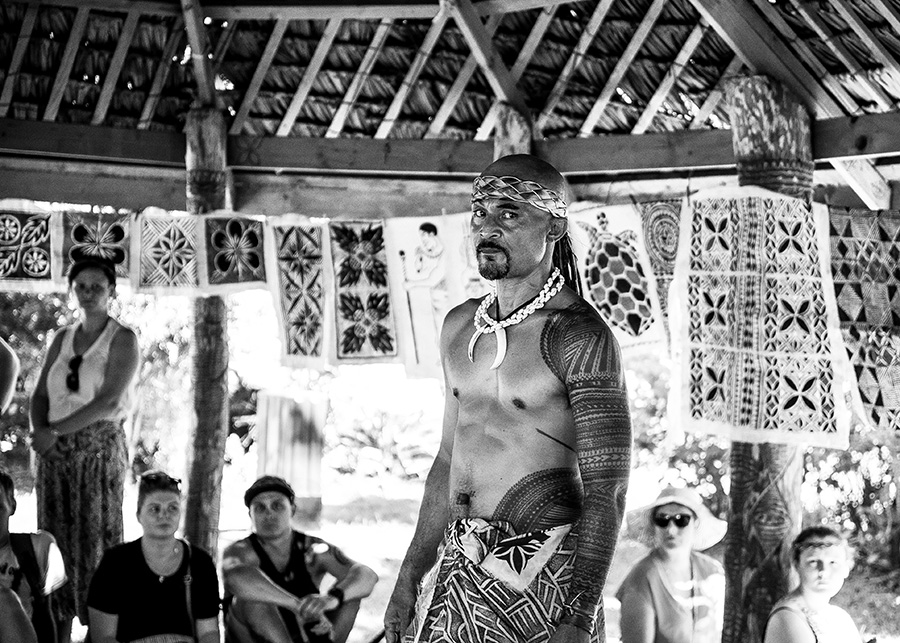

Almost a fortnight ago I landed in Samoa with my partner. We spent long, lazy days drinking from coconuts and freediving in the warm, clear waters of the Pacific Ocean. Our stay was idyllic until Anita and I visited the Samoan Cultural Village in the nation’s capital of Apia. I realise now that was a pivotal moment. We observed a traditional tattoo session firsthand. The word tattoo comes from the Polynesian word tatau, meaning to write. It makes sense that this form of body art originated in Polynesia, because the tattoos we observed that day seemed to crackle with primal energy and meaning. Anita had difficulty thinking of anything else for the rest of our holiday.

Two days before our return to Australia, Anita told me she wanted a tattoo. I was not surprised. Ever since she swam with humpback whales in the Island Kingdom of Tonga she had expressed her desire to get a whale tattoo. But I was not prepared for the idea of it happening right now. During our prior visit to the cultural village, our host made it clear that receiving a tattoo in Samoa is a painful rite of passage. It’s not something to be treated lightly. Not something to do on a whim.

“Tim, I want to get a tattoo before we leave. What are your thoughts?”

I consider Anita’s hazel eyes and silently go through my possible responses. I could tell her I don’t care for tattoos. I could tell her I think most people get tattoos that appear flippant and superficial. If you’re going to permanently mark your skin, it better stand for something! I could also tell her I would never get a tattoo myself. I don’t tell her any of that. After living twenty plus years with her, I’ve cottoned onto the fact not everything is about me.

“Honey, this is about you. Whatever you decide to do, I’ll support you.” There it is. She’s off to the races.

Our host made it clear that receiving a tattoo in Samoa is a painful rite of passage. It’s not something to be treated lightly.

The decision to do something is the most difficult part of anything worthwhile. However, I’m reconsidering this truism while I stare at Anita’s prone form before me, repeatedly whacked with a pointy instrument. Another of my unspoken reservations was the belief that a whale image would not translate well into a Samoan tattoo. After all, whales are usually associated with Tonga. Anita was ahead of me. She abandoned the idea of a whale tattoo an hour before the session. Her decision was not a compromise, it was a remarkable change in plans. She tried to distil the essence of who she was into a few exchanged words with the tattooist. He considered her words and then went to work creating an inked armband to represent who Anita is. No sketched design beforehand, no toing or froing over artwork… straight to it. Anita had completely surrendered to a process. Exquisite pain the price, with no conception of what her arm would look like afterwards.

I sit in nervous expectation of the outcome. I’m not watching a tattoo applied. I’m in church trying to fathom the profound mystery of this liturgy. The priest is writing with blood and ink. My beloved’s skin, his parchment.

And just like that, it’s over. Anita has been replaced by someone else. The Samoan stranger transformed her. His fingers and ink-dipped blade obviously knew her better than I did. The new Anita moves with purpose and confidence.

I’m happy for her. Before we leave, I pay my respects to my previous partner, now left behind in Samoa, the sacred centre of the Pacific.

For an expanded and deeply personal account of this event, please read Anita’s version here (it’s much better than mine).