I’m unsettled. Since last Wednesday evening, I’ve been awash with the sense that I’m part of a tragedy. A big, blue tragedy.

I attended a screening of BLUE, held at the Australian Museum. The film’s director, Karina Holden, introduced her work to an audience packed into the museum’s theatre. Karina, a trained biologist, likened the feeling of watching BLUE to going on a dive. It starts off dark, then gradually becomes lighter and restorative, until we finally surface for air. I’m grateful Karina prepped us, because the next seventy minutes were harrowing.

BLUE opens with an impressive aerial shot of bait fish congregating off a remote beach. The fish form dark, swirling clouds—an omen? The appearance of predators—dolphins and sharks—encourage the dusky fish cloud to part. Bright, light splashed openings rhythmically reveal the sleek forms of the underwater hunters.

A freediver, Lucas Handley, joins the dolphins and sharks to shadow the mass of fish. I marvel at the way the diver’s presence mirrors that of the dolphins and sharks. The bait fish swirl around his invisible bubble, maintaining safe distance. An in-water view replaces the godlike perspective of the aerial camera. This spectacular opening scene situates us, humans, as both observer and predator. How effective a predator? A lot more effective than the shark. In fact, the shark has fared badly.

We next follow Madison Stewart (aka Shark Girl) as she visits a fish market in Indonesia. No, scratch that. Fish market is an antiseptic term. This is a butcher shop for fantastic beasts. A dead Tiger Shark is stretched out on the tiles as a local man takes a sharp blade and removes the magnificent creature’s fins. Valuable appendages for the shark fin trade. Millions of sharks are taken each year to satisfy the need for soup. Madison and the filmmakers don’t point the finger, they document. The malevolence here stems from economic inequality. The shark butchers are poor and apex predators are monetarily worth more dead than alive.

The demand for shark is but one aspect of the expectation that the oceans should feed everyone. BLUE next accompanies Mark Dia, a campaigner who works to uncover the excesses of the seafood industry. Accompanied by footage of industrial scale fishing, Mark highlights the plight of the tuna fish. Tuna, like the shark, are predators too. Tuna are now so depleted in numbers, Mark notes that eating them is like consuming rare snow leopards. Think about that the next time you see rows of canned tuna on the supermarket shelves. Our insatiable appetite for fish has not only impacted shark and tuna stocks, all fish life is in decline. Lucas, the freediver from BLUE’s opening scene notes that during his lifetime, half of all marine life has disappeared.

The demand for seafood crosses borders. Declining fish stocks mean fishing vessels seek opportunity elsewhere and enter waters off limits to their activity. Perversely, the fish caught still end up on our plates. Up to a third of the fish available in our supermarkets has been caught illegally. After fish are caught, nets are often abandoned to drift on the ocean currents. These ‘ghost nets’ ensnare marine life that must return to the surface for air. BLUE presents a nightmarish montage of the results from the ghost nets’ passive labour. Seals, playful creatures dear to my heart, entwined in the unfeeling threads, dead from drowning. More nets, exhumed by Ranger Phillip Mango and his team from a beach in Northern Australia. The sandy mesh, threaded with the desiccated remains of turtles.

As an audience member, I was aware my body was tense and my breathing shallow. While the horror unspooled on screen, I reflected I felt more relaxed when I went to see the film adaptation of Stephen King’s IT. This realisation may have been cause for dark mirth if not for the gut punch that followed.

BLUE checks in on Dr. Jennifer Lavers, a marine eco-toxicologist who works with seabirds. The camera accompanies Jennifer and her team on a night run to investigate shearwater chicks on Lord Howe Island, a remote paradise. A lone, living chick is identified and a tube is gently inserted down its throat. Liquid is pumped into the chick to flush out the contents of its gullet. A nightmare collection of plastic ephemera vomits forth. The chick has been fed plastic debris by its parent, not because the shearwaters are insane, simply because the oceans are now filled with fragmented plastic and seabirds cannot distinguish between it and food. This little chick was fortunate Jennifer found it. Jennifer temporarily relocated the bird and filled its empty stomach with a nourishing squid smoothie. Most seabirds are not so lucky. Almost 1 million of them die each year from ingesting plastic, making them one of the most threatened animals on earth. All because of our addiction to convenient, single-use plastic items.

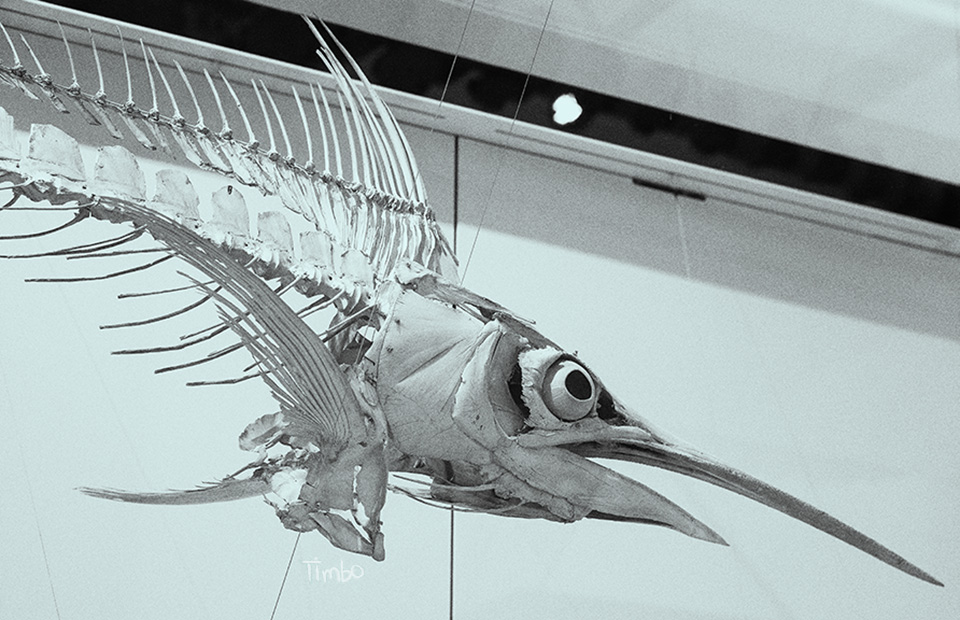

Through a series of brutal vignettes, BLUE has made it clear the problems of the sea are manifold. It was fitting to present this film within the surrounds of the Australian Museum, an institution dedicated to nature and its contents. But as much as I love the museum, I don’t want it and other museums to be the only places left to see evidence of a once rich biosphere.

As frightening as BLUE is, it has caused me to examine my own actions. This seems more productive than despair, which, like anger, seems a luxury none of us can afford right now. If we’re emptying the oceans at an alarming rate, taking less seems like a good start. Tinned tuna is no longer going into my supermarket trolley. I’m unable to justify it.

You also don’t need to go far to find evidence we’re filling the sea with plastic. I took the following photo of a disposable plastic coffee cup lid, just around the corner from Manly Beach, Australia. The lid had bite marks from where fish had sampled it. Since then, I’ve switched to a washable and reusable keep cup. Imagine how much plastic debris could be reduced if we all did this?

Seek out BLUE. Gain an understanding of the pressures the oceans are under. Afterwards, ask yourself, what change can I make today to help the ocean? Feeling BLUE can make the world a better place.

More information on the feature film BLUE can be found here: bluethefilm.org

One Reply to “Feeling BLUE”